The Overpopulation Fallacy: Problems with a Malthusian Approach to Environmentalism

As can be seen consistently throughout various approaches to tackling climate change, the perspective from which one views and explains a problem directly shapes its solution.

Most of the current beliefs surrounding overpopulation originated from one man: Thomas Malthus and his ideas of population theory in his infamous Essay on the Principle of Population – and they exemplify how a poor understanding of the issue can ultimately do a lot more harm than good. While Malthus presents ideas that provide a useful base on which to build and develop an understanding of global environmental change and the relationship it shares with human population growth, his arguments are based on countless unsubstantiated assumptions which ultimately lead to incorrect and alarmist conclusions about population growth in the near future as well as as a skewed understanding of the actual causes of GEC.

While his ideas are seen by modern environmentalists as highly controversial and ultimately counterproductive, Malthus did present a number of significant observations. Malthus provided a set of rudimentary tools and ideas to analyze population growth that form the basis for a more complete understanding of current population theory.

Perhaps most notable was his model of “geometric” (exponential) human population growth. While incorrect as a generality, it does provide a fairly accurate portrayal of historical population growth (in particular the last 200 years). Additionally, it may be not be the root of the problem, however population growth is a part of the problem – an idea supported by notable environmentalists such as Jane Goodall, Sierra Club and James Lovelock. This also forms the basis for Paul Ehrlich’s I=PAT formula which would later be modified to a more accurate formula describing environmental impact (I) as a product of consumption (rather than affluence), technology and population.

Malthus also argued that “the key to avoiding inevitable resource crisis is a moral code of self-restraint”, an idea which Garrett Hardin in his Tragedy of the Commons would later define as a “no-technical solution” problem (a problem that cannot be solved by technology but rather by examining human morals and societal relationships). In his paper, Malthus was referring in particular to the impoverished populations of third-world countries. What he didn’t realize is that this view does accurately describe an aspect of the solution, only that rather than the impoverished this would actually apply to the over-consuming populations of Western civilization.

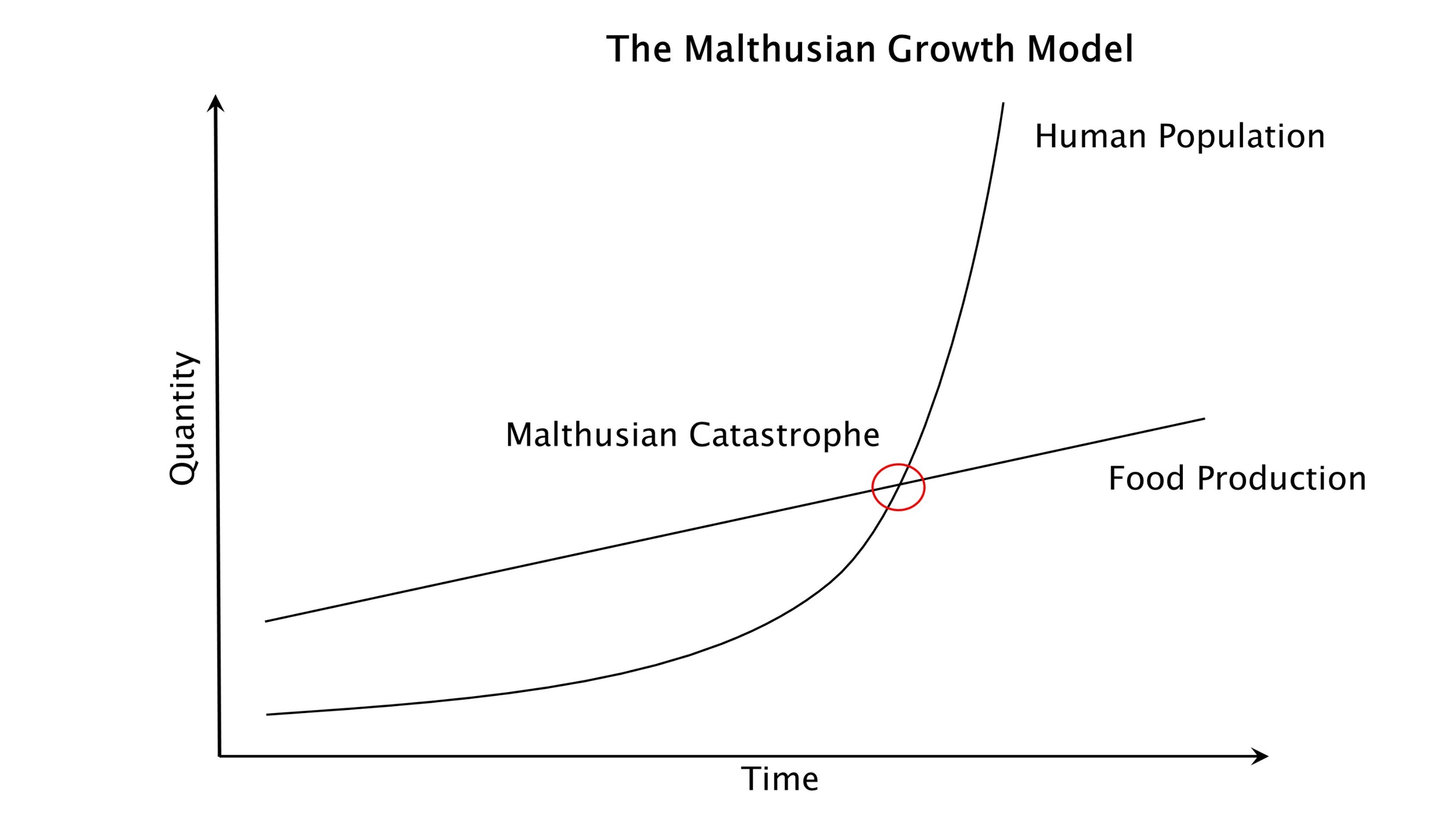

Much like Hardin, despite the strengths in his argument, his solutions were based on a set of false assumptions and these sort of assumptions were ultimately the fatal flaw in his argument. Malthus’s assumptions on which he based his theory were faulty on a number of levels, and this led to alarming and incorrect conclusions about the state of the world. He assumed human population growth mirrored patterns observed in nature, leading him to develop the idea of geometric growth. In reality, this is not the case – historically, population growth peaked between 1960-1970, before gradually declining to under 1%, towards the mythical ZPG (zero population growth). As empirical evidence began to support this, models such as the DTM (demographic transition model) were put forth to describe a more accurate understanding of population growth.

Additionally, he assumed the food base for a growing population was essentially fixed, resulting in human civilization quickly reaching its carrying capacity (the point in which resources can no longer sustain population growth). This was also completely unsubstantiated, and prominent economist Ester Boserup would soon dispel this with her model of induced intensification, showing that the food base is not fixed but rather population would innovate and adapt, intensifying the production and increasing the yield from a single piece of land as the demand grew.

Malthus’s assumptions about the poor and their inability to practice restraint also helped perpetuate the idea that the poor cannot efficiently manage their resources, a notion that leads governments to seize control and privatize land and natural resources with negative environmental consequences. This can be observed in the case of Kissidougou, Guinea where an erroneous view of a small community’s environmental relationship prompted the government to enforce regulations that ultimately hurt the situation (governments had suspected that over time the village had depleted the surrounding territory of forest, yet as observed by Fairhead and Leach, villagers were actually creating and enriching forest land). This can also be seen in Kizmanga, India, where mass evictions executed in order to conserve land actually forced people into poverty, resulting in a high number of poachers which only further degraded the environment.

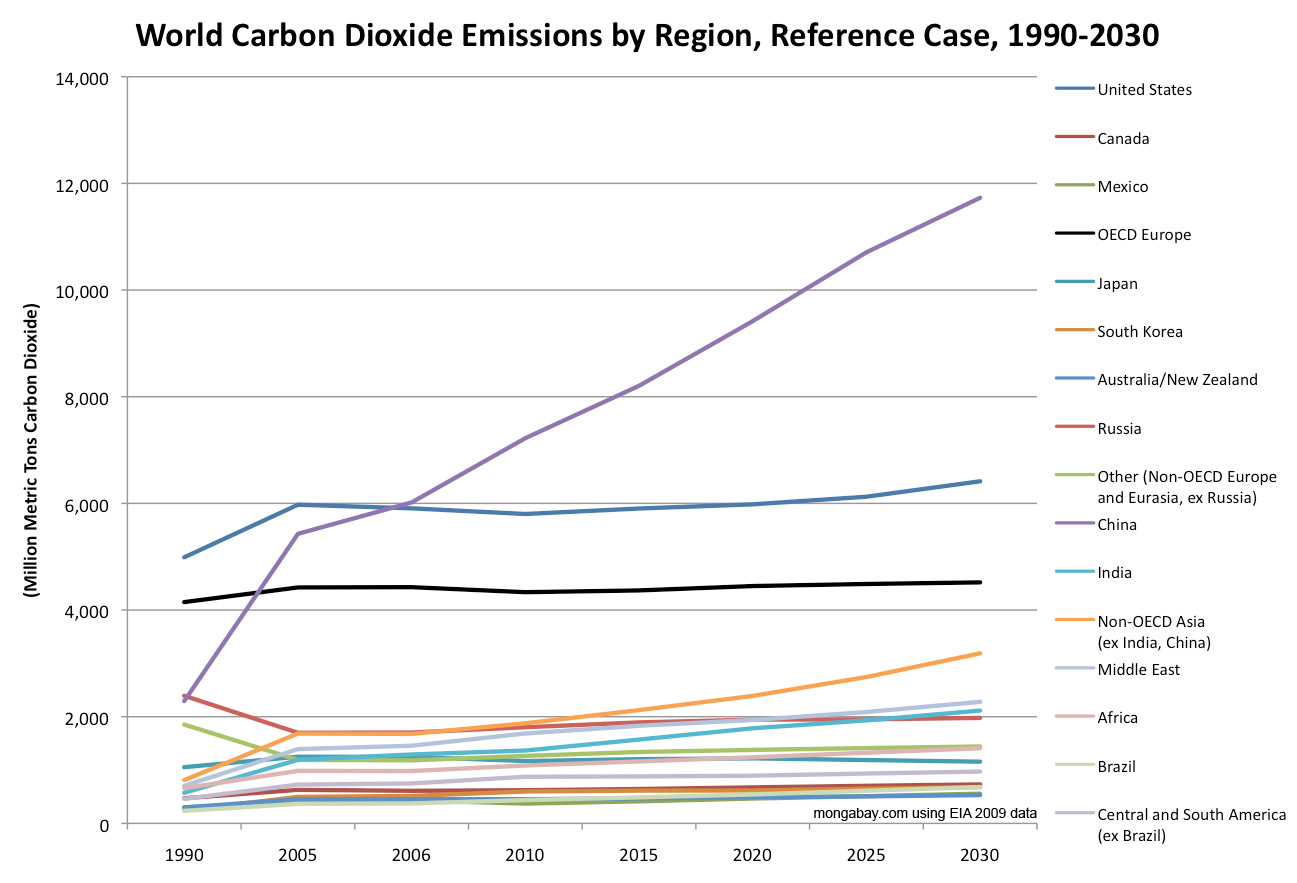

At the heart of his argument, Malthus assumed that environmental degradation corresponded directly to population growth rates, and this was perhaps the most significantly faulty assumption. Empirical evidence clearly refutes this – for example, between 1980-2005, the United States contributed only 3.4% of world population growth, however they made up a whopping 12.6% of global CO2 emissions. In that same period, China’s growth rates have decreased rapidly but their greenhouse gas emission have continued to increase. Ultimately, Malthus focused on the wrong issue – overpopulation was not the problem, but rather overconsumption.

Karl Marx viewed Malthus’s theory as “an explanation for poverty that absolved economic systems, political structures or the actions of the wealthy elite from fault”, and this was by no means inaccurate. Malthus’s arguments supported capitalist systems which directly contributed to further worsen environmental degradation and poor economic conditions, ever perpetuating this cycle in a clear example of what can only be described as the two contradictions of capitalism. The premise of Malthus’s argument was both false and alarming, and the solutions he proposed thus exacerbated the real problem.

Malthus’s assumptions and deeply flawed arguments ultimately created a set of ideals and viewpoints that would set in motion a number of draconian measures and policies to be adopted throughout the world. This includes but is not limited to the strict one-child rule enforced in China, the forced systematic sterilization adopted in India at the hands of Paul Ehrlich and even suggestions of mass sterilization via drinking water contamination.

As aforementioned, his arguments have led to some positive results – primarily as an alert about the serious threat of humanity degrading the planet of resources to an unsustainable point. Ultimately however, while he does put forth a useful basis on which to develop our understanding of environmental change, Malthus undeniably did more harm than good. He provides an important example and lesson on how not to view population growth and the relationship it has with the environment. Once again, how one sees and explains the problem of GEC fully shapes the solution, and Thomas Malthus is an exemplary case of one of the fundamental principles of social environmentalism: how an incomplete understanding of the issue ultimately acts to further the problem itself.